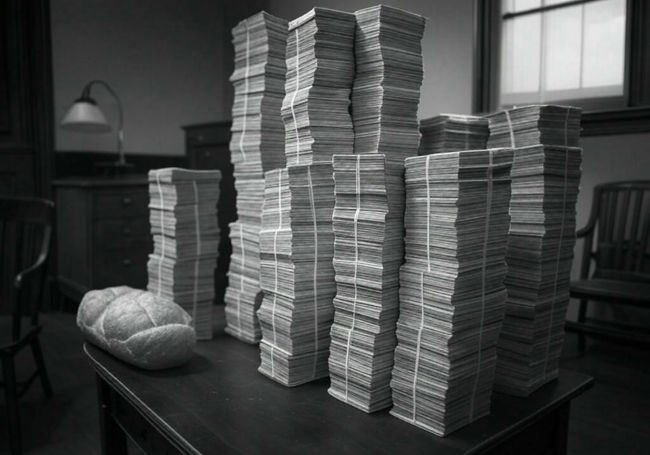

Hyperinflation—an explosive surge in prices, often exceeding 50% monthly—has historically unraveled economies with alarming speed. A coin’s value today might buy only dust tomorrow as currency floods markets unmatched by real wealth. Governments, desperate to fund wars or deficits, have printed money into oblivion, eroding trust and sparking chaos. Savings vanish, wages lag behind soaring costs, and daily life twists into a struggle. In Weimar Germany, wheelbarrows hauled banknotes for bread; in Zimbabwe, trillion-dollar notes fueled fires when their warmth outvalued their worth. These are tales of resilience and ruin from history, not blueprints for today’s world.

How to Spot the Signs of Hyperinflation Early

Recognizing hyperinflation before it spirals could once mean the difference between preparation and panic, though history’s warnings don’t always match modern moments. It often crept in subtly, but certain signals—economic and social—flashed early. Here are five key signs drawn from the past:

Rapidly Rising Prices

What to Watch For: Prices of daily essentials—food, fuel, clothing—doubled or tripled within weeks or months, far outpacing wages. This wasn’t mere inflation; it was a relentless climb.

Historical Example: In Weimar Germany (1921–1922), before hyperinflation peaked in 1923, bread prices soared from 1 mark to 20 marks in a year. By mid-1922, merchants adjusted prices daily, a grim hint of the mark’s collapse ahead.

Observation: Such trends sparked a scramble to shift wealth into tangible assets or stockpile goods before cash lost meaning—a choice rooted in that era’s desperation.

Sharp Decline in Currency Value

What to Watch For: The local currency plummeted against foreign ones, with exchange rates shifting wildly week to week. Imports turned exorbitant as black-market rates surged.

Historical Example: In Zimbabwe (2006–2007), the Zimbabwe dollar’s value crashed, with $1 USD leaping from 250 Zimbabwe dollars to over 100,000 on the black market in a year. This foreshadowed the hyperinflation peak of 2008.

Observation: Those who secured stable currencies like USD early preserved some purchasing power amid that time’s chaos.

Loss of Confidence in the Government

What to Watch For: Trust in economic stewardship faded—protests flared, hoarding began, and officials denied a crisis while central banks printed money unchecked.

Historical Example: In Venezuela (2015–2016), the government dismissed inflation warnings despite bare shelves and endless queues. The central bank’s rampant bolívar printing eroded faith, with inflation hitting triple digits by 2017.

Observation: Self-reliance, like gardening, emerged as trust in solutions waned—a story from their struggle.

Shortages and Panic Buying

What to Watch For: Shelves emptied as suppliers hoarded or demanded foreign cash. Consumers snatched up goods, fearing worse scarcity.

Historical Example: In Yugoslavia (1992), before hyperinflation hit 1 trillion percent monthly in 1994, Belgrade shops faced sugar and oil shortages in 1991. Panic buying cleared stores, a prelude to the dinar’s fall.

Observation: Stockpiling and community networks softened the blow of vanishing supplies in those desperate days.

Wage Demands and Labor Unrest

What to Watch For: Workers clamored for frequent raises or goods as pay lagged prices. Strikes and workplace bartering rose.

Historical Example: In Hungary (1945), pre-hyperinflation saw Budapest workers demand daily wage adjustments by mid-1946, as the pengő lost value hourly. This unrest preceded the world’s worst hyperinflation that year.

Observation: Tradeable skills became lifelines as cash faltered—history’s lesson from that time.

Monitoring these signs once allowed decisive action—converting savings, growing food, or uniting with neighbors—before hyperinflation tightened its grip. These were moves born of their moment.

Preparation Before Hyperinflation

In history’s grip, preparation softened the harshest blows. Here’s how people responded, shaped by their time:

Protecting and Diversifying Wealth

Hard Assets and Precious Metals: Gold and silver held value when paper failed. In Weimar Germany (1922–1923), shops refused marks, but gold coins bought bread. In Zimbabwe (2006–2009), informal miners bartered gold nuggets for food, though theft loomed. Risks existed—during the U.S. Great Depression (1933), gold was confiscated under Executive Order 6102, a cautionary note from the past. Learn more about historical wealth preservation tactics in Wealth Preservation in Times of War and Revolution.

Foreign Currencies: Stable currencies shone as local ones sank. In Venezuela (2016–present), U.S. dollars from remittances or black markets bought goods when bolívars failed. In Zimbabwe, rand flowed near South Africa’s border, outpacing the dying Zimbabwe dollar by 2009.

Cryptocurrencies: Digital assets emerged later. In Venezuela (2017 onward), Bitcoin and Tether (USDT) preserved savings via platforms like LocalBitcoins, though crackdowns loomed—a lifeline then. Explore how modern tech shapes wealth in The Great American Bitcoin Race.

Reducing Reliance on the Local Financial System

Foreign Bank Accounts: Offshore funds escaped collapse. In Zimbabwe (mid-2000s), some moved savings to South Africa or the U.K. before controls tightened, accessing them later. In Argentina (2001), offshore account holders dodged the corralito’s freeze.

Debt Strategies: Fixed debt shrank as prices soared. In Weimar Germany, pre-1923 mortgages vanished in value, repaid with worthless marks—a farmer’s loan once worth a cow later bought a loaf.

Building Skills and Self-Reliance

Gardening fed families in Venezuela (2016–present), with Caracas balconies yielding beans amid shortages. In Cuba’s Special Period (1990s), urban farms grew half of Havana’s vegetables by 1998. Repair skills thrived in Zimbabwe (late 2000s), with mechanics bartering fixes for maize—skills that mattered in their day.

Establishing a Support Network

In Venezuela (2018), Maracaibo neighbors shared garden harvests. In Argentina (2001), “trueque” barter clubs swapped goods for services, ballooning to 2.5 million users by 2002—a community fix for a broken time.

Stockpiling Essential Supplies

In Venezuela (2015–2016), families hoarded rice before shelves emptied. In Hungary (1945–1946), sugar and flour stashes fueled barter as the pengő crashed. In Cyprus (2013–2014), wood stockpiles warmed homes during power cuts—hoarding born of necessity.

Survival During Hyperinflation

When hyperinflation hit, people fought daily to preserve value and secure essentials. History reveals how survivors adapted, shaped by collapse:

Abandoning the Local Currency

Immediate Spending: In Weimar Germany (1923), workers spent wages mid-shift as prices soared—bread costing 100,000 marks at noon hit 200,000 by dusk. One Berliner recalled rushing to shops before evening doubled the cost again.

Foreign Currencies: During Yugoslavia’s 1993 crisis, with monthly inflation at 1 trillion percent, Belgrade markets demanded German marks. A Niš retiree swapped her entire pension for one mark, which outvalued her dinar savings instantly.

Establishing Alternative Trading Systems

Humans have always found ways to trade, driven by an innate need that even modern ingenuity can’t fully escape through self-reliance alone. In times of crisis, this instinct birthed unconventional systems, born of desperation.

Historically, barter and informal economies emerged as lifelines when currencies crumbled. In Zimbabwe (2008), rural families traded chickens for soap or maize for labor—a practical response to a worthless Zimbabwe dollar. A Mutare farmer once swapped a goat for a month’s cooking oil, bypassing cash entirely. In Venezuela (2018), Caracas vendors accepted U.S. dollars smuggled from Colombia, with one noting, “Dollars meant food; bolívars meant nothing.” In Weimar Germany (1923), towns like Altona issued “notgeld”—emergency tokens of paper or porcelain—to keep bread and coal moving when the mark failed.

Finding or Forming Alternative Currency Sources

Foreign Currencies: In Venezuela (2018), Caracas vendors leaned on smuggled U.S. dollars. One said, “Dollars meant food; bolívars meant nothing.”

Cryptocurrencies: By 2019, a Caracas café owner took Bitcoin via QR codes, noting, “It’s not perfect, but it beats watching bolívars vanish”—a workaround of its time.

Rationing and Resource Management

Stockpiles: In Zimbabwe (2008), Harare families stashed beans, rationing them over months. A mother cooked once daily to save fuel, stretching each meal’s warmth.

Government Rations: Venezuela’s CLAP boxes (2016) brought sporadic rice and pasta, often tied to loyalty. A Caracas resident said, “It wasn’t enough, but it was something.”

Relying on Local Production

Urban Gardening: In Venezuela (2017), Petare slum dwellers grew manioc on rooftops. One turned her balcony into a herb garden, trading basil for soap.

Small-Scale Farming: In Zimbabwe (2007–2009), Matabeleland families lived off millet and sorghum, insulated from urban collapse.

Ensuring Security and Solidarity

When hyperinflation eroded trust in institutions, neighborhoods turned inward, pooling strength to weather the storm. In Zimbabwe’s Bulawayo (2008), where families felt security faltering, neighbors organized watch groups to protect homes and gardens. One member recalled, “We couldn’t trust police, so we trusted each other.” In Venezuela (2019), Caracas residents ran “ollas comunitarias,” pooling scraps into soups that fed dozens. A volunteer said, “We ate less, but no one ate alone,” a testament to solidarity in scarcity.

Innovative and Unconventional Approaches

Hyperinflation forced creative solutions beyond the norm, born of their moment’s madness:

Digital Currencies: In Venezuela (2018), Bitcoin use surged, with platforms like AirTM converting bolívars to digital dollars. A Maracaibo shopkeeper said, “Crypto saved my business when banks failed”—a tale from then. In Zimbabwe (2009), traders used EcoCash for USD payments, dodging Zimbabwe dollars.

Community-Based Economies: Argentina’s 2001 “créditos” powered 5,000 barter clubs—swap a haircut for flour, tracked by points. A Rosario participant said, “It wasn’t money, but it worked.” Brazil’s URV (1994) indexed prices to a stable unit, easing panic before the real debuted.

Novel Financial Instruments: Venezuelan merchants (2018) pegged prices to the dollar via WhatsApp, adjusting bolívar rates daily. A Caracas grocer explained, “We think in dollars but take bolívars at the day’s rate—it’s survival math.”

Social and Psychological Aspects

Hyperinflation strained minds as much as wallets:

Community Support: In Zimbabwe (2008), Harare churches handed out mealie-meal, their halls becoming shelters. A pastor said, “Faith and food kept us sane.” In Venezuela (2017), families shared tips on finding flour or chicken, turning scarcity into a group effort.

Mental Resilience: Small victories mattered—grabbing rice in Venezuela or fixing a bike in Zimbabwe felt heroic. A Caracas mother said, “Each barter was a win; it kept despair away.” For more on mental fortitude, see The Art of Inner Dialogue.

Post-Crisis Recovery

Recovery required strategy after the storm:

Currency Reform: Germany’s Rentenmark (1923) reset the game—one Rentenmark equaled 1 trillion marks. A Berliner traded hoarded coal for a flat with just a few new bills. Zimbabwe’s 2009 dollarization steadied prices; a Bulawayo trader with $100 USD restocked and thrived.

Rebuilding Savings: In Brazil (post-1994), real estate prices dropped in real terms—those with foreign cash bought cheap. A São Paulo investor snagged three apartments with dollars saved abroad, tripling his wealth in a decade. Dive into wealth rebuilding in How Wealth Is Formed and Sustained.

Community Rehabilitation: Venezuela’s councils (2020) planned food co-ops post-crisis, rebuilding trust. A Caracas organizer said, “We survived by sharing; now we rebuild together.”

Critical Evaluation

Every tactic had flaws:

Gold Risks: Weimar Germans traded gold for bread, but theft (Zimbabwe’s bandits) or confiscation (U.S. 1933) struck. A Harare miner lost his nuggets to robbers, saying, “It was safer, but not safe.”

Barter Limitations: Zimbabwe’s barter covered basics but faltered for complex needs—trading a cow for medicine rarely worked. A Mutare farmer sighed, “I had goats, not pills—what then?”

Capital Controls: Cyprus (2013) froze accounts, trapping savings. A Nicosia retiree said, “My pensions vanished in the bank—I had nothing.” Argentina’s “corralito” (2001) hit hard, though offshore savers dodged it.

Legal Barriers: Venezuela jailed dollar traders (2018), pushing deals underground. A Caracas vendor whispered, “Dollars fed us, but the law hunted us.”

Adaptability, not one perfect fix, was key to survival in those times.

//

Disclaimer: These are historical examples, not modern advice. What worked then fit its time—today’s context differs vastly. Consult experts for current decisions. No liability applies here for actions taken based on these stories.